Message in a Bottle Myths

By Clint Buffington

The history of messages in bottles bubbles over with true stories that almost defy belief, as well as myths and hoaxes that have escaped scrutiny for too long. Bottled messages have indeed saved lives, led to marriage, survived the ravages of the sea for seemingly impossible lengths of time, and even laid the groundwork for oceanography. Wonderful as this history is, it gets muddied, even degraded, by myths that go unchecked.

How, then, do we differentiate between facts and the many popular myths and legends about messages in bottles? Simple: We dive into the historical record.

Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, the Armada Portrait, circa 1588 (Anonymous).

MYTH I

Perhaps the most famous message in a bottle myth dates back to the reign of England’s Queen Elizabeth I. According to this legend, the Queen—upon learning that members of the British Navy as well as her “spies on the continent” sometimes sent sensitive military information back to England via message in a bottle—appointed a new position in her government: Official Uncorker of Ocean Bottles. She proclaimed that anyone caught opening a message in a bottle besides her Official Uncorker could be put to death, due to the highly secret, sensitive information in the bottles.

Doesn’t that seem a little…odd to you?

Let’s think through it: If you were the leader of a powerful country and you learned that your soldiers were sending sensitive military information out to sea in leaky bottles that could wash up anywhere and be found by anyone, what would you do? Would you pat them on the back and encourage their behavior by creating a government position for someone to open whichever bottles were lucky enough to reach your country’s shores?

Of course not. It would be so unthinkably irresponsible to handle secret military information this way, that the myth has it backwards: If Queen Elizabeth I discovered her soldiers had entrusted secret military information to messages in bottles, it would have been those soldiers who were hanged, not the innocent fishermen who opened the bottles. When you get right down to it, the whole idea is just plain silly.

French novelist Victor Hugo thought so, too—and he should know, because he invented this whole absurd myth to provide some dark humor for one of his novels, The Man Who Laughs, published in 1869. In the novel, one of Hugo’s characters—a comical, ambitious figure called Barkilphedro—desperately wants to be part of the royal court. Knowing that a duchess named Josiana is jealous and competitive, he tells her that, long ago, Queen Elizabeth I had appointed an “Official Uncorker of Ocean Bottles,” and that she should too. He convinces her to appoint him to this absurd position, granting him a salary, lodgings at the Admiralty, and a place at court.

In their book Flotsametrics, Curtis Ebbesmeyer and Eric Scigliano traced the myth back to Hugo’s book, and no further. Just in case there was even a grain of truth to this legend, I contacted the UK’s National Archives. They explained that, in Queen Elizabeth’s time, if there had been a law stating that anyone caught opening a message in a bottle besides the Official Uncorker could be put to death, it would have been recorded and shared with the public through an official proclamation. After all, how else would the public know not to open bottled notes? They also explained that official positions appointed by the Queen can be found today in something called the “Patent Rolls Index,” which includes a record of occupations under Elizabeth’s reign.

Here’s what the folks at the National Archives told me when they looked around for evidence related to this myth: “We have searched the C 66 Patent Rolls Index relating to Elizabeth I, where occupations are listed, and had no success in finding a reference to an ‘Official Uncorker of Ocean Bottles.’ A search was also made in the publication Tudor Royal Proclamations’ Volume III, The Later Tudors (1588–1603, edited by Hughes and Larkin, Yale University Press, 1969) for a reference to a Proclamation on this subject, but again, without success.”

Translation: No such position ever existed, and no such law ever existed.

The legend has been beloved for decades. It has inspired stories, art, and even a lovely children’s book, The Uncorker of Ocean Bottles by Michelle Cuevas. But, as the UK’s National Archives explains, the position only ever existed as a work of fiction.

Ancient Greek philosopher Theophrastus, depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493.

MYTH II

A similarly famous myth concerning the origins of messages in bottles states that the first “known” messages in bottles were sent by the ancient Greek philosopher, Theophrastus around 310 B.C. Alas, this is not true. Although this legend circulates widely on the Internet, including among prestigious media outlets like National Geographic, Wikipedia, and others, not one scrap of proof has ever been produced to substantiate this claim—because none exist. Ebbesmeyer probes the Theophrastus myth in the section of Flotsametrics entitled “Urban Legends of the Sea.” He writes: “Theophrastus’s Bottles. For years, I cherished Gardner Soule’s Men Who Dared the Sea, which recounted how Aristotle’s protege Theophrastus released bottles in the Strait of Gibraltar to see if a current flowed from the Atlantic into the Mediterranean. Soule included footnotes for many parts of his book, but none for his chapter on Theophrastus…And the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica gave the same account. To confirm it, I contacted a group of scholars at Rutgers University, who were assembling all of Theophrastus’s known writings. They graciously investigated but could not verify that he released drifters.”

Curious to learn more, I picked up Ebbesmeyer’s trail. I am not sure where Ebbesmeyer and Scigliano found an Encyclopedia reference to Theophrastus using bottled messages to study ocean currents, because in versions of 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica available online, no such reference exists.

Next, I studied the book Ebbesmeyer cherished, Gardner Soule’s Men Who Dared The Sea. Sure enough, Theophrastus is mentioned, and so are bottles—but, crucially, not messages. Here’s what Soule actually wrote: “Plato had taught Aristotle. At his school in Athens, the Lyceum, Aristotle taught a student named Theophrastus. Sometime before 300 B.C., Theophrastus began tossing bottles and marked seaweed into the sea to see where they would drift.”

Soule claims that Theophrastus tossed “bottles and marked seaweed into the sea.” Not messages in bottles, but “bottles.” Even if this were true—and nothing in the historical record suggests that it is—there is a world of difference between empty bottles and bottles containing messages.

Conveniently, Soule never provides a source for his claims about Theophrastus. Goodness knows where he got the idea that Theophrastus did these things. But then, with Soule, we have on our hands a man who wrote passionately about the Flathead Lake Monster (described variously as whale-like, or like a giant eel 30 feet long, possibly with antlers, depending on who you ask), and whose writings about cowboys and the American west are regarded by prominent historians as “full of errors” and historically inaccurate. Soule’s publications covered cryptozoology, the American west, Antarctica, and Christopher Columbus; he probed the existence of monsters, UFOs, and more. He was wildly curious about our world. But a specialist, he was not. Nor was he an authority on either Theophrastus or the history of messages in bottles. This is likely why his accounts of both are…well, “full of errors.”

According to Ebbesmeyer and Scigliano, and according to the Theophrastus scholars they contacted at Rutgers, the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, and even Gardner Soule himself, whatever Theophrastus may have done to study ocean currents, he certainly never put messages in bottles and sent them to sea.

A painting of Benjamin Franklin from 1778 (Joseph-Siffred Duplessis).

MYTH III

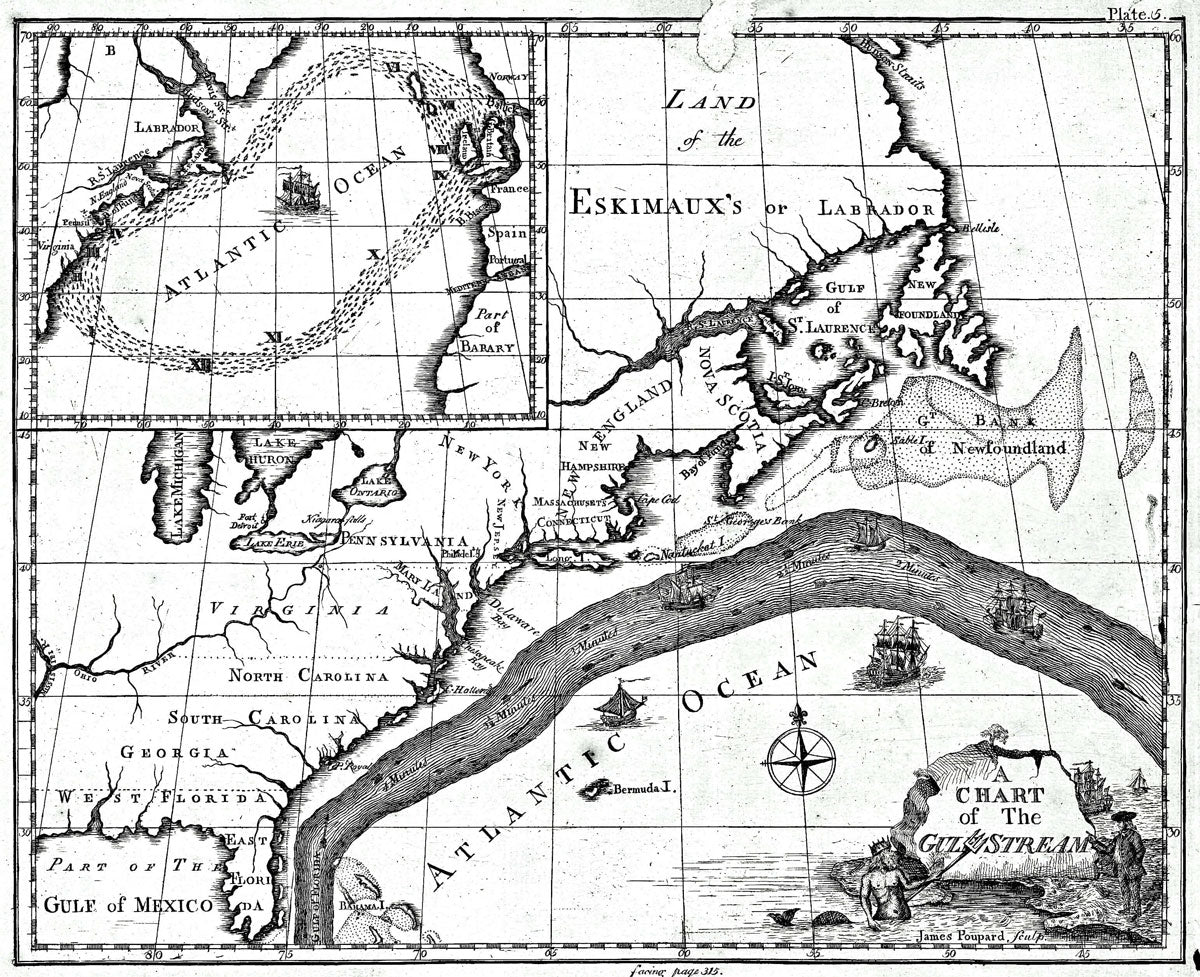

A third popular myth states that Benjamin Franklin sent messages in bottles in the Gulf Stream to see where they would end up, and, from this information, he created the first accurate map of the Gulf Stream, known as the Franklin-Folger map.

To debunk this myth, I spoke with Karie Diethorn, curator of Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia and a Ben Franklin expert, during the filming of my documentary, The Tides That Bind: A Message in a Bottle Story (directed by Nick Natalicchio) in 2018. During our talk, Diethorn described the claim that Benjamin Franklin sent messages in bottles as “false,” plain and simple. She added that he did not “discover” the Gulf Stream, but rather was simply the first to document it accurately. “His process for doing that did not involve messages in bottles,” Diethorn explicitly explained. Rather, it involved “interviewing whalers and fishermen who used the Gulf Stream in plying their trade.”

Diethorn went on to explain that Franklin “interviewed his one particular cousin, Timothy Folger, about the Gulf Stream,” and that is why the map they produced is called the Franklin-Folger map, not just the Franklin map. “Franklin crisscrossed the Atlantic for four different round trips in the course of his lifetime, and he got really interested in the Gulf Stream. Every time he went back and forth, he would perform all kinds of meteorological and oceanographic experiments because he was interested in the data. So, he was looking at the color of the water, he was gathering temperature information, and the way he did that was he suspended a glass thermometer over the side of the ship because the water in the Gulf Stream is much warmer than the water in the regular Atlantic. He could see, both in temperature and in color, where the Gulf Stream actually was. I think the message in a bottle myth comes from people misreading or misremembering that he was taking water temperature measurements with a glass thermometer.” In the end, this is a classic myth: part true, part imaginary. Ben Franklin did chart the Gulf Stream, but he never sent messages in bottles.

Earliest known map of the Gulf Stream, 1769 (Benjamin Franklin).

These three myths have captured our imaginations for decades, and with good reason. They are powered by the same blend of magic and reality that makes actual messages in bottles so fascinating. The real shame of the internet’s obsession with spreading these myths is that they overshadow the true history of messages in bottles, which is even more amazing. We do a disservice to the history of ocean science, to British history, and to American history if we let these stories spread, disguised as facts when they are myths.

I hope we can lay these myths to rest, and instead appreciate the incredible true history of messages in bottles. It’s full of stories like that of Ake and Paolina Wiking, who married via message in a bottle—as did Annie and Nils Elffers and others. Also, the story of Maud Butler, a young Australian girl who dressed as a soldier and snuck aboard a troop ship bound for the western front of World War I so she could fight, and when she was discovered, became the subject of several messages in bottles sent by Australian troops on her ship (she actually did this twice). Speaking of Australia, there’s the story of Alfred Deakin, Australia’s second prime minister—a real-life head of state who was actually drawn into a real-life message in a bottle mystery (unlike Queen Elizabeth I) when a washed-up note claiming to be from marooned Australian sailors nearly caused him to order a ship to go search for them. The message turned out to be a hoax and the search abandoned, but it was a rare case of a message in a bottle reaching the desk of a nation’s leader.

There’s the story of the French women—Stephanie Barneix, Alexandra Lux, and Flora Manciet—who crossed the Atlantic Ocean on a paddleboard, a feat so mind-boggling and physically challenging no one had ever even attempted it before them and no one has since. They set a world record with their crossing, and, together with their documentarian, Lucie Robin, sent a message in a bottle along the way to commemorate their journey (which I was delighted to find 10 years later). There’s Dr. Eilidh Stimpson of Edinburgh, Scotland, who was astonished when plumber Peter Allan discovered a 135-year-old message in a bottle (technically the world’s oldest, though not found on a beach) under her floorboards during renovation work, bearing a wistful message of two builders from long ago: “Whoever finds this bottle may think our dust is blowing along the road.” These stories are not only lovely—they are true, which makes them even more magical.

Messages in bottles provide a classic example of the idiom: the truth is stranger than fiction. In this case, I would add: The truth is more wonderful, bewildering, enchanting, and inspiring than fiction. As mesmerizing as these message in a bottle myths are, they have nothing on the true history of this lovely and bizarre phenomenon that has connected people around the globe and across generations—and that’s the truth.

This article appeared in the Beachcombing Magazine July/August 2023 issue.